Jafar Panahi – one of the most acclaimed film makers ever to come out of Iran has been ordered jailed for six years and banned from making films for twenty.

Jafar Panahi – one of the most acclaimed film makers ever to come out of Iran has been ordered jailed for six years and banned from making films for twenty.

Globally recognized for his internationally acclaimed movies like ‘OFF SIDE’, ‘CRIMSON GOLD’, ‘THE CIRCLE’, ‘THE WHITE BALLOON’ and ‘THE MIRROR’, Jafar Panahi is one of the most influential filmmakers in the Iranian New Wave movement. He has gained recognition from film theorists and critics worldwide and received numerous awards including the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival.

Because of his outspoken nature, Panahi have gotten himself in trouble with Islamic regime before. His troubles began in July of 2009 when he attended a ceremony mourning the protesters killed for expressing concern over alleged irregularities during the recent fraudulent Presidential elections in Iran. He was arrested at the time but later released, though banned from leaving the country.

He was arrested again in February of 2010 and accused of illegal gathering, collusion and spreading propaganda against the current regime of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. These are the ‘crimes’ for which he has now been convicted.

In an interview in September, Panahi had said: “When a filmmaker does not make films, it is as if he is jailed. Even when he is freed from the small jail, he finds himself wandering in a larger jail.”

The harsh sentencing was seen as a blow to the international cinematic community and a warning to Iranian artists to stay away from politics. Panahi was a vocal supporter of the opposition.

Prominent Hollywood filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Soderbergh, Juliette Binoche, Oliver Stone and Frederick Wiseman have condemned his imprisonment and signed a petition for Panahi’s immediate release.

Panahi was named a member of the jury at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, but because of his imprisonment he could not attend and his chair was symbolically kept empty.

The cinema of Jafar Panahi is often described as Iranian neo-realism. Regardless of how one chooses to categorize his powerful work, the unprecedented humanitarianism of Panahi’s films cannot be denied. His films are urban, contemporary and rich with the details of human existence.

Panahi’s first feature film came in 1995, entitled THE WHITE BALLOON. This film won a Camera d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and Institute of Moving Images – the Film School has listed this movie as one of the best 50 family films of all time.

His second feature film, THE MIRROR, received the Golden Leopard Award at the Locarno Film Festival.

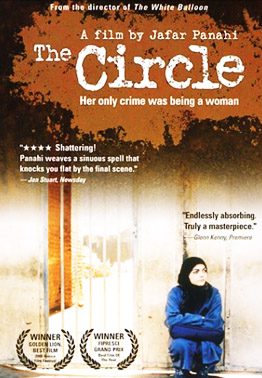

His most notable offering to date has been THE CIRCLE (2000), which criticized the treatment of women under Iran’s Islamist regime.

Jafar Panahi won the Golden Lion, the top prize at the Venice Film Festival for THE CIRCLE, which was named FIPRESCI Film of the Year at the San Sebastián International Film Festival, and appeared on Top 10 lists of critics worldwide. But the film is banned in Iran.

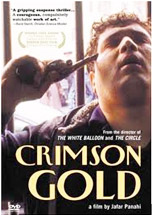

Panahi also directed CRIMSON GOLD in 2003, which brought him the Un Certain Regard Jury Award at the Cannes Film Festival.

During that time Panahi was detained in the JFK airport, New York, while taking a connection from Hong Kong to Montevideo, after refusing to be photographed and fingerprinted by the immigration police. After being chained and waiting for several hours, he was finally sent back to Hong Kong.

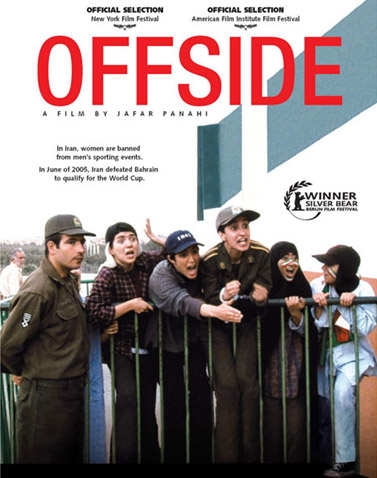

Panahi’s next film OFFSIDE (2006) was selected for competition in the 2006 Berlin Film Festival, where he was awarded with the Silver Bear (Jury Grand Prix).

OFF SIDE is a film about girls who try to watch a World Cup qualifying match but are forbidden by Islamic law because of their sex. Female fans are not allowed to enter football stadiums in Iran on the grounds that there will be a high risk of violence or verbal abuse against them.

The film was inspired by director Jafar Panahi’s daughter, who decided to attend a game anyway. The film was shot in Iran but its screening was banned there.

On 20th December 2010, Jafar Panahi, after being prosecuted for “assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic,” was handed a six-year jail sentence and a 20-year ban on making or directing any movies, writing screenplays, giving any form of interview with Iranian or foreign media as well as leaving the country.

Iran’s culture minister said that Panahi was sentenced because he “was currently making a film against the Islamic regime and it was about the events that followed election.”

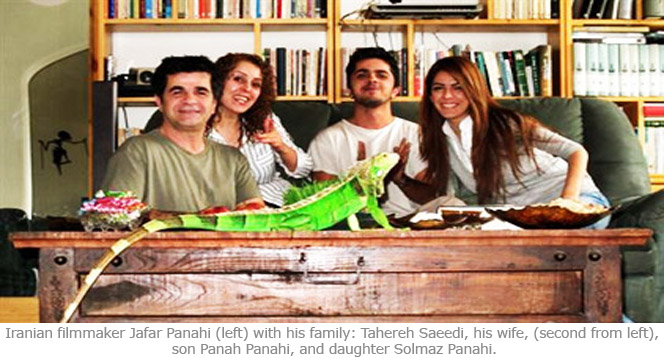

But Panahi’s wife, Tahereh Saeedi, denied that he was making a film about post-election events, saying: “The film was being shot inside the house and had nothing to do with the regime”.

Through His Son’s Eyes

Panah calls his father his “best friend” and “one of the kindest people I know on this planet.”

“All my friends agree with me,” says the 26-year-old, a lanky young man with an abundance of thick dark hair often styled in a Fonzie-like sweep off his forehead.

Jafar Panahi was born in 1960 in a poor area in south Tehran, one of eight children.

“My dad was living in a very crowded house during his childhood,” Panah says, but he “fell in love with cinema” at an early age, working after school from the age of 12 in order to make money to see films.

“He was always really in touch with the limitations and poverty that surrounded him,” says his son. “It was from that time that the kind of social perspective toward cinema took shape in his mind.

“He wants to use the art of cinema to show the pain of human beings in different periods of time,” he says. “By showing the limitations, the poverty, sadness, difficult times in human history — this is the way to achieve a humanistic cinema. And what is more poetic than a humanistic moment?”

All of Panahi’s films are influenced by a cinematic movement called “neo-realism” that first emerged in post-World War II Italian film. It is characterized by a grittier cinematic style depicting ordinary human life, in contrast to the gaudy, packaged style then in vogue.

Throughout his career, Panahi often used nonactors in an attempt to show what he called, in an interview with the film journal “Senses of Cinema,” the “truth of society.”

Panah Panahi says the 1947 film “The Bicycle Thief” by Italian director Vittorio De Sica was crucial to his father’s development. “It was this film,” he says, “that taught him cinema”.

WATCH the trailer for Jafar Panahi’s “The Circle,” which won the Golden Lion at the 2000 Venice Film Festival:

He often invoked a sequence in the film, his son explains, in which the main character follows the thief to his home and is moved when he witnesses the thief’s life of poverty and the struggles he has with his family relationships. From that moment on, the thief becomes human in the main character’s eyes.

“I think this sequence reflects Jafar’s character and his cinema,” says Panah Panahi.

“Doubtless, the effect of that Vittorio De Sica sequence makes Jafar look at his prosecutors the same way the main character was looking at the thief,” he says. “He will forgive them and not carry anger in his heart. I wish these politicians would look at people like Jafar and learn some humanity from them.”

As a teenager, Jafar Panahi enrolled in an educational institute established by famed Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, one of the best-known Iranian directors in the West and a towering figure on the Tehran film scene. Kiorostami also taught film at the school, and it was there that he first met Jafar. Their friendship, Panah says, continues to this day.

At 20, Jafar Panahi’s studies were interrupted by the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988). He served in the military from 1980-1982, producing a war documentary for Iranian television during that time. After completing his deployment, he enrolled in the Tehran College of Cinema and Television, where he met his future wife, Tahereh Saeedi, who was working as a nurse.

The couple has two children, Panah and a daughter, Solmaz, who was briefly imprisoned after her father’s arrest but later released. She is now studying theater in Tehran.

As he was completing his studies at university, Panahi worked as Kiarostami’s assistant for the acclaimed 1994 film “Through The Olive Trees” and a year later, in 1995, the then-35-year-old Panahi produced his first feature film, “White Balloon.” The film, based on an original script by Kiarostami, effectively launched Panahi’s international film career.

Now aged 50, Panahi’s imprisonment and cinematic restrictions promise to impede his work, but Panah Panahi says his father, even in jail, still sees beauty in the world around him — as only a filmmaker can.

He remembers visiting the country’s notorious Evin prison, where his father is being held, and seeing him standing under a mulberry tree surrounded by guards but with his attention elsewhere — he was looking upwards, plucking berry after berry off the tree.

We at Institute of Moving Images strongly condemn the imprisonment of any dissent voice anywhere and urge the Iranian authorities that like artists everywhere; Iran’s filmmakers should be celebrated, not censored, repressed and imprisoned.

2 Responses to Filmmakers should be celebrated; not censored, repressed & imprisoned